For centuries, colour has assisted humankind in making sense of the world – everything from knowing when ripe fruit is ready to eat, to branding political parties to labelling perceived terrorist threat levels. Whether we’re aware of it or not, the complex visual language of colour informs, entertains, provokes, warns, unifies and comforts us. As the abstract expressionist painter Hans Hoffman once said, “The whole world, as we experience it visually, comes to us through the mystic realm of color.”

Like a beacon, colour cuts through the commotion, enabling us to identify and catalogue data. It acts as a powerful mnemonic, one we turn to time and time again. When branding different floors in a parking garage, designers often add individual floor numbers in custom colours by exit doors, helping visitors to remember where they left their vehicles. They’ve learned that people have difficulty recalling their floor number but remember their floor colour. Numbers are a familiar means of organizing information, whereas colour coding is less common and more memorable.

Colour coding is often logical. The segmentations on a forest fire warning sign, for example, appear rational as they advance from cool to hot tones as the risk of fire increases. Methods of ranking skill levels that use light-to-dark colour progressions, as implemented in martial arts belts, also make sense. And then there are those colour indicators that are less noticeable. Did you know that hardhat colours indicate specific trades or experience on a construction site? Supervisors wear white hats, technical advisors blue, safety inspectors red, labourers yellow and new employees wear green.

Colour also helps to label adverse situations. If you are depressed or unwell, they say you are suffering “the blues.” This phrase comes from the 17th-century term “blue devils” to describe the hallucinations that came with a hangover. Eventually, “the blues” came to mean a state of depression. The term “in the red,” another way of saying money loss or debt, refers to a time when bookkeepers would use red ink to accentuate negative financial entries.

Catastrophic events such as the Black Death and yellow fever came by their monikers earnestly. Between 1346 and 1353, the Black Death pandemic killed an estimated 75 – 200 million people. It takes its name from the black boils and tumours that covered those stricken by the plague. Yellow fever refers to the yellow cast of a person’s skin and eyes, two of the outwardly visible symptoms of the mosquito-transmitted disease. Both names, although descriptive, are not necessarily hurtful, certainly not in any personal way. To say someone has yellow fever is a statement of fact – it’s a universally accepted medical term. However, there are instances where things can get malicious.

Painting: The Scarlet Letter by Hugues Merle / 1861

Throughout history, groups or communities have resorted to chastising others with badges of shame – incidents where a symbol conspires with a colour to identify or categorize an individual spitefully. An icon does the heavy lifting in the following examples, but colour weighs in and adds to the overall derogatory message. Why these specific icons? More importantly, why these particular colours?

During the seventeenth century, dissenters of the Church of England, known as the Puritans, settled in America to escape persecution and establish a more “Godly” existence directed by a strict interpretation of the Bible. In doing so, they had little, if no tolerance for moral indiscretions. In his book The Scarlet Letter, published in 1850, Nathaniel Hawthorne tells the tale of Hester Prynne, a woman found guilty by the Puritans of committing adultery. As punishment Hester must wear a scarlet “A” on her dress as a badge of shame. The letter stands for adulteress.

Although The Scarlet Letter is a work of fiction, it reflects actual events in the New England towns of Plymouth and Salem between 1650 and 1670. Those communities had passed a law requiring adulterers “to wear two capital letters, A and D, cut in cloth and sewn on the uppermost garment on the arm and back; and if at any time they shall be found without the letters so worn while in this government, they shall be forthwith taken and publicly whipped.”

The scarlet letter was a symbol created by the Puritans to humiliate the accused and dissuade others from committing a similar offence. By mandating that the letter “A” be red, the Puritans made sure the emblem would stand out on the predominately muted clothing of the time. Prominent in the Bible, red is associated with, among other things, blood and sin. No doubt the Puritans’ “scarlet letter” was referencing the Book of Isaiah 1:18, “Come now, and let us reason together, says the lord, though your sins are like scarlet, they shall be as white as snow; though they are red like crimson, they shall be as wool.” The Puritans knew this would make an effective badge of shame and that the Biblical connotations of the colour would add to its gravity.

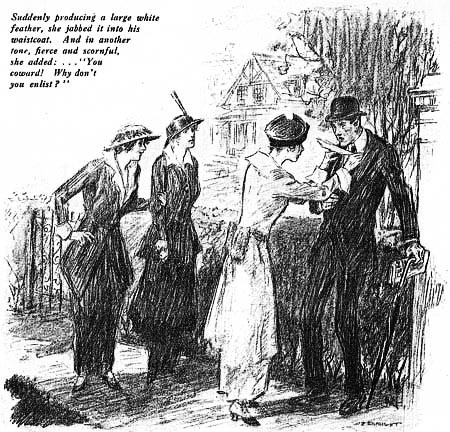

Image: Arnold Bennett / Collier’s Weekly

Not long after the start of the First World War, it became common for women in Britain to approach young men not in military uniform and present them with a white feather. Started by avid war supporter Admiral Charles Fitzgerald, the “White Feather Brigade’s” mission was to humiliate men who had not enlisted in the war. During this period, men were expected to fight and society, for the most part, looked down on those who chose not to. This form of public shaming spread to other countries of the British Empire, including Canada.

The white feather, as a symbol of cowardice, is said to have its origin in cockfighting. Apparently, white-feathered roosters are poor fighters. There are many recorded incidents of servicemen unjustly receiving white feathers while home on leave and out of uniform. Other recipients, who had been deemed unfit for war, were traumatized by the public shaming. Made to feel emasculated, some even committed suicide.

In warfare, the colour white indicates passiveness – as demonstrated by the use of white flags to signal neutrality, surrender and peace. When you add to the mix the colour’s association with purity and innocence it makes for a powerful badge of shame during times of armed conflict.

Image: The United States

Holocaust Memorial Museum

Arguably, the most damning form of persecution surfaced in Nazi Germany during World War II. In 1941, Jewish people, six years and older, were forced to wear a yellow Star of David cloth patch on their outer garments. Displayed on the left breast or the back, it became known as the “Yellow Badge” or the “Jewish Badge.” Located within the Star of David was the word “Jude,” German for “Jew.” The symbol both stigmatized the German Jewish population and monitored their movement. Jewish people have been singled-out with yellow tagging throughout history – starting as early as the 9th century. Yellow is a complex colour and has many meanings. Its negative connotations are at work here, emphasizing caution, weakness, cowardice and betrayal.

In 2007, police stations in Bangkok devised an unusual badge of shame. Authorities threatened wayward officers with the punishment of wearing a pink Hello Kitty armband in the precinct for several days. The hope was this action would act as an effective deterrent to others. “Simple warnings were not enough,” said acting chief Pongpat Chayaphan, “Kitty is a cute icon for young girls. It’s not something macho police officers want covering their biceps.” Many immediately see pink as signalling femininity, associating it with little girls’ clothing, princesses, fairies, and dolls. Hello Kitty may be suitable for a young girl’s backpack, but it becomes a statement of ridicule when seen on the arm of male police officers. This proposed badge of shame accomplished its purpose. There were no documented cases of pink Hello Kitty armbands ever being worn by Thai police officers.

Image: Associated Press

The letter A, the Star of David, a feather, and Hello Kitty are widely acknowledged symbols. The context in which each gets presented impacts the message they champion. When used to promote a contentious situation, one can intensify a symbol’s meaning by pairing it with a particular colour and its historical and cultural connotations.

Red may represent passion and love, but when emblazoned on one’s chest as the letter A, it becomes a crimson stain that shouts “sinner.” White connotes purity and virginity, but during WWI, a white feather earmarked you as a coward. The Nazis transformed yellow from a colour of optimism into a sickly, degrading shade of despair. And pink’s feminine side threatened the masculinity of image-conscious cops.

Colour lightens up our lives and brings joy, but it can have the opposite effect. Just ask prisoners how it feels to wear clown-like vivid orange jumpsuits. The more we understand the complex meanings of each colour, the more we become aware of each one’s negative characteristics. This explains why sometimes this dazzling spectrum of light, this phenomenon we call colour, sadly has the potential to humiliate, alienate and promote hatred.